One of the joys of being a Middle Earth enthusiast is that, over forty years after the death of J.R.R. Tolkien, new works from his papers continue to be published - a remarkable feat for any author. No matter how regularly this happens, news of a new Tolkien book still manages to surprise as well as delight. My own joy at hearing of the forthcoming publication of “Beren and Lúthien,” edited by Tolkien’s son and literary executor Christopher Tolkien, left me quite literally jumping up and down with excitement, to the mild bemusement and possible chagrin of my co-workers.

Tolkien considers the tale of Beren and Lúthien to be one of the most important in his mythology. Beren, a mortal man, encounters and falls in love with the immortal elf Lúthien, though their union was forbidden by her father. To win his approval, the two embark on a dangerous quest to retrieve one of the Silmarils, jewels prized by the elves, from the very fortress of their great enemy. The story was one with which Tolkien personally identified; his marriage to his wife was initially forbidden by her guardian, and the names of Beren and Lúthien would be engraved upon their tombstone. He began writing the first version of the legend a century ago while serving in the First World War, and he would return to the tale again and again for the remainder of his life. Tolkien was never able to finish the tale, like so much of what he wrote. Ever the perfectionist, he was never quite satisfied with the end result. The great work of Christopher Tolkien in this book is to draw together parts and versions of the tale scattered throughout his father’s papers, giving the reader a view into how the tale evolved over the decades.

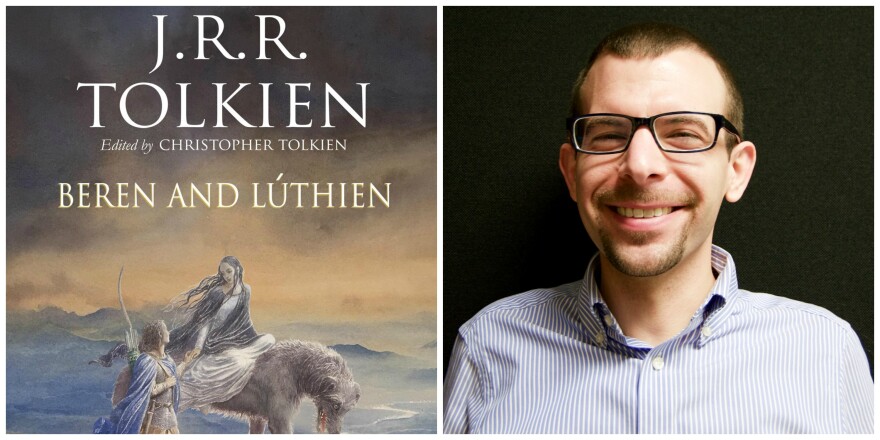

While I got my hands on a copy fairly soon after the release date, I took my time reading the work. It is a book to be enjoyed slowly, not hurriedly. The sections of verse are beautifully written, a reflection of Tolkien’s long study of language and the mythologies of Iceland and Scandinavia. Paintings and line drawings by Alan Lee, a regular illustrator of Tolkien’s works, add a lot to the narrative. While sometimes the various pieces of the work contradict each other, that isn’t a drawback. Instead, this makes Tolkien’s stories more like what he hoped to create for his homeland: a mythology for England. The myths of other cultures, after all, often contradict each other. The tale is a hauntingly beautiful one of love, loss in the face of a great evil, and hope even in the darkest of places, recurring themes in Tolkien’s writings. Beautifully sad too is the likelihood that one of the earliest written tales may well be the last published. Christopher Tolkien is 92 and further publications seem unlikely. But we’ve come full circle in many ways - while we could always wish for more from the scribe of Middle Earth, we still have so much. It will have to be enough.

Reviewer Brady Clemens is the district consultant librarian at Schlow Centre Region Library.