On this episode of Take Note on WPSU, we'll talk with Geoff O'Gara, the director of the documentary "Home from School: The Children of Carlisle." It's about a boarding school for Native American children in Carlisle, Pennsylvania that ran from 1879 to 1918. It was funded by the federal government to assimilate native children into European-American culture. More than 10,000 Native American children from 140 tribes attended this boarding school during its nearly 40 years in operation.

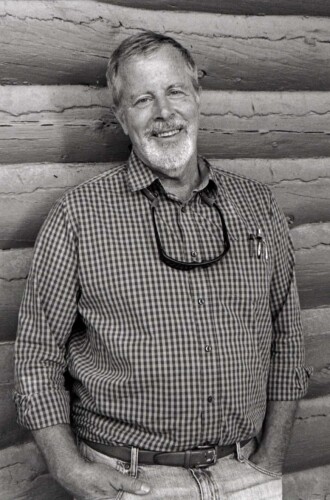

Emily Reddy

Geoff O'Gara, thanks for talking with us about the film "Home from School."

Geoff O'Gara

Thank you, Emily, good to be here.

Emily Reddy

So, "Kill the Indian. Save the man," that was the motto of the founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, this boarding school for native children. What did the school do to get the "Indian" out of them?

Geoff O'Gara

Well, let me give you a little background first on Richard Henry Pratt, who founded the school and where that phrase came from that he made rather famous, or infamous, I should say. Pratt was a military man. He'd served in the Indian Wars in the late 19th century, the Indian Wars being when the United States government attempted to quell the wandering and somewhat rebellious tribes that were primarily in the plains in the West. He did that and worked with various tribal members as scouts for the military, and then also with what they called the Buffalo Soldiers, black soldiers who were recruited and served in the Army. So Richard Henry Pratt's conviction was when he said, "Kill the Indian in him and save the man," that Native Americans were as capable as European-Anglo children to learn and, you know, be effectively involved in society. But his idea of how you to that was to erase all the remnants of their own culture, their own history, and essentially teach them to be very much like the white children in the Anglo-European community that essentially was running the United States. So in a funny way, not funny at all, really, but in a serious way, he was a believer in the capabilities of Native Americans, maybe more so than a lot of others at that time in the late 19th century. But his idea of how to engage that was essentially to erase their own history and culture and turn them into little model white citizens by putting them in uniforms, cutting their hair, taking away their traditional clothing, and, most essentially, not allowing them to speak their own language. That was kind of the core principle in the boarding school at Carlisle and those that imitated it that sprung up around the country, primarily in the West.

Emily Reddy

And the school used to be a military base. You have a lot of photos, and some actual footage of those children walking in lines in uniforms. It's very striking.

Geoff O'Gara

Yes, I think the... Carlisle particularly had that military model because Richard Henry Pratt had been in the military, but all the schools -- and those images, we've got the motion pictures, we've got our from various boarding schools around the country -- all of them did this kind of regimented way of life. You know, you got up at a certain time. You went to the dining room. You were segregated by gender. Everything was very orderly. And the day was very orderly. There were, literally, you know, bugle calls at Carlisle, when it was time to get up in the morning, when it was time to begin classes. They all worked as well. They were in various sort of trades for half the day where they were learning to be carpenters, or to do some other useful thing. In some cases domestic skills, so that they could become essentially domestic servants. One of our scholars who spoke about it in the documentary, points out that this really was not the kind of education that prepares you for college, that prepares you for higher learning. So whatever good motives Pratt might have had, the school ultimately was training kids to essentially fill service roles in the larger economy.

Emily Reddy

Carlisle was the first off-reservation native boarding school. Some of these kids came days on the train all the way from the Western United States. Were their parents sending them? Were they abducted? How did they end up at the school?

Geoff O'Gara

It was a mixture of motives. There were some very coercive methods of getting children removed from the reservation or from their tribe to the school, which was part of the mission. Because, again, we're just coming out of the Indian Wars, and so a lot of these children had served as runners, as helpers to their parents, to their fathers and uncles and even grandfathers at places like "Greasy Grass," Custer's Last Stand. And so they wanted, the motive behind these schools was to get those children away from the tribal environment, and essentially turn them into something else. There were, though, in many tribes there was a motivation at their end as well, which was, they knew that they had to deal with this new culture. They knew that they had to deal with the government, the American government, the United States government. And they wanted some of their children to have language skills. They wanted them to understand the shape of the culture of the civilization that was being imposed on them. So they at the tribal end of things could negotiate with them, could get the best deal for their people possible. So, you know, in a way, it was kind of like sending your child away to learn a particular skill that they could then bring back and use for the good of the tribe. It didn't always work out that way. In some cases, just the act of being removed for so many years, in many cases many years, from your home environment, from your family from your tribe, created a kind of alienation on both sides. Where these kids would come back no longer kids. And their language wasn't quite the same anymore. Their idea of how to deal with the world was a little different. And they didn't fit in that well. So you had a very mixed result out of all this, even from the tribal perspective.

Emily Reddy

And some of these native children died at the Carlisle boarding school often from diseases that they were more vulnerable to. In fact, 238 children died at Carlisle.

Geoff O'Gara

Yeah, and it's a number that is a little bit soft. Because as we found out when the Northern Arapaho went back to to retrieve the remains of the three boys that died there, some of those graves have a single marker and more than one body underneath it. So as they get further into this, and not every set of remains is likely to be disinterred. Some tribes object to that. But as they look further, I think we may find there are more children buried than we thought. I might add too that a lot of children when they got sick, they were sent home. So I think Pratt and others who ran the school, were aware that this didn't look very good to have a cemetery at a school for, you know, elementary and high school aged kids. And so they would find these kids getting sick with primarily European diseases like tuberculosis. And when they got to a certain point would be like, "Well, time to go home," and they'd send them back. So I think if you really wanted to crunch the numbers, you would find that a great many children who went to Carlisle died after they went back to the reservation. It's a really sad story. I mean, the vulnerability of those children to those diseases would be kind of obvious. I mean, we know smallpox, other things that were introduced from Europe and elsewhere to the North American continent, you know, hit Native Americans particularly hard because they had no antibodies, no resistance to that. In addition, there's emotional deprivation. These are children who've been taken away. I mean, if you look at the pictures, and interestingly enough, Pratt had a deal with a local photographer. So almost all of the young people who arrived at the school were photographed as they arrived, still in their native regalia. And you look at those faces, and you just think, well, there's a child who may have just traveled a week on a train, from a place he had never journeyed far from before and certainly never in a train to arrive at a place where everybody is dressed differently. Everybody's hair is cut. Everybody looks differently. And then be expected to adjust. I mean, these are children. It's kind of scary to imagine what it must have been like. And their relatives today who went to retrieve the remains in the case of the Northern Arapaho that was one of the first things they thought about. You know, what must it have been like for those children to have made that journey and to have arrived at this place, with no prospect of when they would go home and what was going to happen next?

Emily Reddy

And that story is one of the major focuses of your documentary. The Northern Arapaho tribe in Wyoming, who travel here to Carlisle, Pennsylvania to retrieve the remains of the three boys from their tribe who died there in 1882 and 1883. But the military, which now houses the U.S. Army War College there, tells them it's a historical site. They can't have the remains. I actually want to play a clip from the promotional video about that struggle to get those remains back.

VIDEO:

Yufna Soldier Wolf: We have letters from my grandpa who wrote here, and my dad who wrote here, my uncle who wrote here, requesting for our children back.

Dr. Jacqueline Fear-Segal: It is the first time, the very first time that any of the native nations have succeeded taking ownership of this history and taking ownership of their students that they lost and taking them home again.

Millie Friday: We're not waiting no longer for anybody to come save us. We're gonna save ourselves.

Yufna Soldier Wolf: We're still rehashing this. Why can't we be focusing on science, math, engineering, you know. There's so many other things that we could be focusing on. But we can't do that until this has been... we've healed from it.

Emily Reddy

And the military did eventually agree to give them those remains. For the first time.

Geoff O'Gara

Families had been trying for a long time to get the Army to release those remains. It's controversial within tribes as well, though, because, you know, disturbing the dead. It's something that we all might be sensitive to, they can be very sensitive to and some tribes have so far elected not to take the same steps that the Northern Arapaho did. But Yufna and her crew at the Tribal Historic Preservation Office, they just persisted. And every blockade every hurdle that was put in front of them, they did it. They filled out the forms, they followed the rules, they answered all the questions, they think the Army was a little surprised at their persistence. They just wouldn't give up. But, you know, to the Army's credit, at least their eventual credit, they did finally say, "Okay, you can come and take those remains, take those children home." It came as a shock for us as filmmakers, because I had been talking to Yufna about this story, thinking maybe I'd write about it or something. I didn't really know if it was going to be a documentary. But also thinking it's going to take a while before anything happens, if anything ever does. And then all of a sudden, you know, in the summer of 2017, the Army's like, "You can come." And Yufna's like, "We're getting on a plane. We're going." And we're scrambling to find cameras and find people to go with them. And but you know, that in a way made it a more exciting story, because it was such a breakthrough. And, and so much of a reward for persistence. That they wouldn't give up. And as Yufna says in the clip that you played, they're not just trying to kind of relive the past and talk about the greatness of the old days or anything like that. They're trying to resolve old issues that have caused pain and a kind of suffering within the tribe for generations, so that they can move on. And the ultimate hope that Yufna expresses over and over again, is children be free of those kinds of nightmares from the past, unable to look ahead and think what do I want to become? You know, I can be a lawyer. I can be a doctor. I can do all those things. So it's a matter of learning, and then relieving the burden of that history. So that they can have a future.

Emily Reddy

And you're there to document it, when they they do dig up these these remains. And the surprise of the event is one of the graves has as the wrong remains in it. It's an older person. And and so they can only take home two of those of those boys.

Geoff O'Gara

I mean, you could still say that's a triumphant moment, but I can tell you what it was like, because, again, they were very generous. They let us be everywhere with our cameras, including in the motel room where the young people were when they got the news that they in fact work to be able to bring Little Plume home, one of the three boys who died. Yeah, what had happened was, frankly, there was just a misidentification of gravestones. One was placed over the wrong plot. We actually found that with the help of some researchers from Dickinson College. We found these various maps from the past that showed where the different burials had taken place. Because the cemetery had already been moved once from one part of the Carlisle barracks to another. We knew it. And in fact, I remember Betty Friday and I both talking about it beforehand. And like that isn't the right one, is it? And her trying to get the Army to realize that and just not getting any recognition. So yes, they dug up one of the wrong graves. There were two Apache children in there, both older than Little Plume would have been at the time he died. And so they knew it was the wrong one. The forensic archaeologists and anthropologists who were working there on this, were good hearted people who felt terrible about what had happened. And I think everybody said, "Boy, we got to take a break. I mean, this has been so emotionally draining. Got to go back to Wind River, back to the Reservation in Wyoming. But we're going to come back. We're going to get that third child and bring him home as well." And they did.

Emily Reddy

It was a year later.

Geoff O'Gara

Yeah.

Emily Reddy

I found it interesting that these boys died, you know, so long ago that no one living would have ever met them. But that doesn't seem to matter to their tribe. There's this connection between those generations. What was that like seeing that or, as they told it to you?

Geoff O'Gara

I mean, it gets very personal, and I'll get to that in a moment, but to speak from what I can of the of the tribe's perspective on this. You know, Nelson White, one of the elders, one of the four old men of the Arapaho tribe and the keeper of the pipe, said that the spirits are still there. They're still roaming around. There's still this feeling and this very strong belief that those boys aren't gone. They are there. They're not home yet. And so I think, yeah, there's a very real connection, that these are not, you know, photographs or apparitions or anything like that. But these are the boys. They are still in spirit with us, and need to be taken care of. On a personal level, as filmmakers, we made a decision early on that we would not have voices in this. There was going to be no omniscient, I hate to say it, "Ken Burns" narrator there. There was just going to be the voices of the people who lived the experience. So you are hearing from them, their feelings about these children and about this whole effort and how it happened. But from my perspective, working with them and being with them throughout this, I look at that picture of the boys -- the children, girls and boys -- who arrived from Wind River, Shoshone and Arapaho children, and I just can't stop seeing those little faces, just the emotions in them. That sort of bravery looking at the camera, which would have been also strange to them. But standing there with the pipes they brought as gifts, not knowing what was lying ahead for them. I mean, I can't stop coming back to those. And I think, for anybody, I think who looks at those photographs, those children are very much alive, very much alive. But when you hear Yufna and others talk about them, it is intensely personal.

Emily Reddy

If you're just joining us, we're talking with Geoff O'Gara, the director of the documentary "Home from School: The Children of Carlisle." It's about a boarding school for Native American children that ran from 1879 to 1918 in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. I feel like there's been a lot of talk about these schools recently because hundreds of unmarked graves were found this summer on the grounds of native boarding schools in Canada. So these schools existed in other countries, too.

Geoff O'Gara

Yes, one of my co-producers, Sophie Barksdale, is from Australia. And Australia had a system not unlike this of schools for indigenous peoples that were designed essentially to break them apart from their land base and their culture and their families. In Canada, most of what they called residential schools were run by churches, or affiliated with churches. And I think it began in early this year, May and June of this year, they found hundreds of children that were buried in unmarked graves. I mean, it's just tragic. Carlisle, in a funny way, is a little more decent in that there are at least markers, that the children are named. But I have to say, I would not be surprised when you look around the country, and at the history, the number of boarding schools, which I'll get to in a moment that there were in this country, not even in Canada, but in this country. I think we're going to find there are more, not just cemeteries but probably some unmarked graves here as well. We started on this project over four years ago. So at that time, boarding schools were not taught in the classroom. They're not in the history books, for the most part. And it was kind of a story that nobody knew about. It's just coincidental in an ironic and sad way that the news of the Canadian burial sites came out this summer, just as we were beginning to wrap up our story and our documentary, and kind of put it all in the headlines in a big way. There were over 250 boarding schools in this country, nobody realizes how vast this was. Some of them were on reservations. Many of them were run by church groups. Some of them like Carlisle and several other federal boarding schools were off reservations and were not affiliated with churches, but did include church going as part of their process. There were, gosh, three boarding schools on Wind River, in Wyoming, on the Reservation in Wyoming. One with the Episcopal Church, one run by Jesuits, and briefly a federal boarding school as well. So even within the reservation, there were children who were taken away from their families, you know, again, taught often in English. Just a tough experience that so many children of that era going forward, from the 1880s forward, experienced in this country.

Emily Reddy

And you end your documentary by talking about present day native boarding schools. They seem to be a far cry from the Carlisle school in the late 1800s, early 1900s.

Geoff O'Gara

They are. I mean, it's an interesting thing to note that Native American youth today actually have a pretty wide array of choices for education. That doesn't mean they're getting necessarily the great education. But it does mean, unlike the time that we're talking about when the children went to Carlisle, they actually have some options now. That includes schools on reservations, often funded by the Bureau of Indian Education, which is the successor to the federal agencies that funded Carlisle. It includes still some missionary-run boarding schools. It includes public schools, schools that are within whatever state system that they're within, that received funding not unlike a public school that we see in many communities. And they include some remaining federal boarding schools. There are three or four of them left. They are quite different. I'm not going to say they're by any means perfect. But for young people who, for various reasons, may need to get away from their home environment, from a reservation environment that isn't working for them. this is an option. They can go to the Sherman School in California. They can go to Chemawa, in Oregon. They can go to Flandreau in South Dakota. So they do have some options. That said, and at those schools, by the way, language is taught and encouraged. Although they include children from many different tribes. So you're not going to go there and get, you know, be taught Lakota or Arapaho for that matter, because it's going to be selective. But you will learn about native languages. They won't be suppressed. At any rate, those schools still exist. But they're very underfunded. I can't give you the per capita rate of investment that we make in the children who go to those Native American boarding schools today. But it doesn't compare to what most of our children are getting at public schools, certainly not at private schools elsewhere. So, you know, if one wanted to campaign for just good education -- I don't even mean it as a makeup for the tragedy of the earlier boarding schools -- I just mean, we're going to have boarding schools, let's fund them well. We should look at that. The federal government should look at that.

Emily Reddy

In 2021, the U.S. Department of the Interior announced the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative to review the legacy of these Native American boarding schools. So it seems like this is a reckoning that is really just beginning.

Geoff O'Gara

I think that's right. I mean, I think Deb Haaland, becoming Interior Secretary, first Native American to serve in that role, is huge, and should make a real difference. And she has pushed that, just as she pushed an initiative in Congress to set up a Truth and Healing Commission, which never got through Congress, but that's been reintroduced again this year. So on a number of fronts, there is an attempt to kind of come to grips with the history, the legacy, and I think the the impact today on Native Americans of this boarding school history. We'll see where it goes. I mean, I don't want to say commissions are a dime a dozen. They're not. They can be meaningful. And I think certainly to dig into that history a little bit, explore, look further, because as I say, from what I've learned this history, I'm guessing we don't yet know all of the lives lost in the boarding schools of the past. So there's things we need to still find out. The Commission, the various efforts to do this will certainly help in that direction. We'll just have to see how far they go, how far they get. But it's a good step. It's a step we have to take. Truth and healing, it's being done around the world. It's what actually sparked in Canada, the discovery of those grave sites. Those were actually Native American groups, funded by the government through truth and healing, to go and look and see what happened at these different boarding schools. We should think about this in this country as well. You have to deal with this history. That's something I've certainly seen and learned from the Native Americans who are struggling to move beyond it. You need to understand it first. You need to learn from it. You need to be honest about it. And then you can go forward.

Emily Reddy

I talked about your documentary with John Sanchez, a Penn State associate professor of communications. He's Ndeh Apache and part Yaqui as well, and he teaches American Indian and the Media classes. I asked him to react to the documentary and how you'd told the story. And I want to play his reaction for you. It's a couple of minutes long.

I got to give him a gold star, you know, one for bringing this out into the open. You know, it's always hard for native people to do this, you know, because then it's seen by media and by the United States, you know, a lot of times politicians as Indians just crying about something. "And what are they crying about this time?" Well, now they're crying about their children, or of their ancestors that have been buried in graves some unmarked graves at boarding schools. And nobody gives a damn, you know. And we know that we can't do it by ourselves. We're not a part of the dominant culture. People think that we are, but we're not. We have our own culture, our own languages, our own government. You know, the things that we do are our own. And so nobody listens to us. And so the director has done a good job of bringing this out into the open, you know. And we need help like this, you know. We need help from non Indian people to bring it out into the open. So it's not just us saying, "Hey, this is wrong." You know, now you've got other people saying, "You know what? This is an interesting story. And how come nobody's addressed it before?" Well, we've been crying for it for a long time. But the director brings it out in a good way. So people can look at this and say, "Oh, my God, I never thought about this before." And the only thing I ask is at the end of the film, is, if you're not Indian, if you're part of the dominant culture, black or white, you know, or whatever. What I'm hoping is that people of European descent, you know, look at this and go, "Oh, my God, what if that was my child?" That's all I'm asking, you know, and I think the director leaves it right there, you know. Or "If that was my grandfather's son, or my great grandfather's son. You know, that's my grandfather, that I never got to know, because he went to boarding school, he was forced to go to boarding school." I think the more people that see this are going to go, "I never thought about that. I never thought about that."

Emily Reddy

I guess I'll just ask your reaction.

Geoff O'Gara

Well, those those are really generous comments. You know, I think, as John knows, these are stories that within the Native American community have been told for ages. Interestingly, a lot of the older members of the tribes tend to be reluctant to talk too much about a boarding school experience, particularly if it was oppressive, if it was really hard, They don't want to discourage their children from getting an education by frightening them with that kind of a story. So, oftentimes, even within tribes, it's been somewhat repressed. I can only say again that this is a story that we didn't really tell. The people who lived it are telling it. And it's their generosity to share a story that they just felt... the elders said this openly that normally this is not something they would share. But they really felt the story needed to be out. It needed to be told. And always with the idea that it's a way for those young people to move on to better lives. They've got to know the past. We all have to know the past. We non-Indians need to know the past. For me, the greatest reward of this was that feeling coming out of this story that many people, young people who were part of the delegation that went back to Carlisle, older people like Yufna, they really were moving on. Man, Yufna's in law school now. I mean, there's lots going on in people's lives. It's not static at all. And I think dealing with history is something we all need to learn to do. It's a big step and a positive step.

Emily Reddy

Geoff O'Gara, thanks for talking with us.

Geoff O'Gara

Emily, I appreciate it very much.

Emily Reddy

Geoff O'Gara is the director of the documentary "Home from School: The Children of Carlisle." It's about a boarding school for Native American children that ran from 1879 to 1918 in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. During the nearly 40 years the school was open, more than 10,000 native children attended it. You can watch "Home from School" on WPSU-TV Tuesday at 9 p.m. and Wednesday at 2 p.m. For this and other episodes of Take Note, go to WPSU.org/takenote.