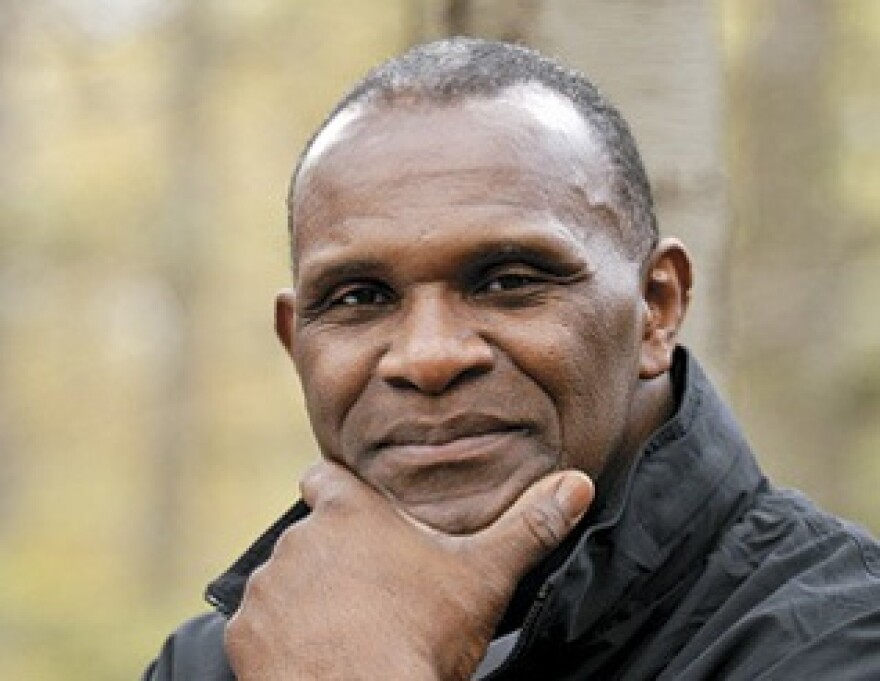

NFL Hall of Famer Harry Carson played 13 years with the New York Giants, 10 of them as team captain. We’ll talk with him about his hard-hitting career as inside line backer, about living with post-concussion syndrome, and about why he says if he could, he wouldn't do it all over again.

TRANSCRIPTION:

SATALIA: Welcome to Take Note on WPSU; I'm Patty Satalia. NFL Hall of Famer Harry Carson may be best known for his 13-years as inside linebacker with the New York Giants, 10 of them as team captain, but his activities off the field are just as noteworthy. Carson suffered from numerous concussions in his hard-hitting career and still deals with symptoms from Post-Concussion Syndrome.

He’s the author of “Point of Attack” and “Captain for Life," and an ardent advocate for concussion awareness. We’ll talk with him about life before and after football, and about why he says if he could, he wouldn't do it all over again!

SATALIA: Harry Carson, thanks for joining us.

CARSON: Thank you.

SATALIA: You suffered at least a dozen concussions in your hard hitting professional career and possibly as many as 18 if you count college and high school. In 1990 you were diagnosed with Post Concussion Syndrome. Explain what that is and how you're doing.

CARSON: Well you know I was having some issues once I transitioned out of football.

SATALIA: In '88.

CARSON: In '88 I started doing CNN, ABC Sports, I was doing college football and I would lose my train of thought live on the air or I would have blurred vision or I would have any number of things; headaches, you know, bouts of depression and I couldn't really figure out why. And so I went to my family doctor annual physical, I passed the physical with flying colors and my doctor asked, okay everything is okay is there any other problems, and I said no, everything's good.

He said, “Are you sure?” I said, well, yeah I've been having these issues and so

he referred me to a specialist. I went through two days of testing and the result came back that I had mild Post Concussion Syndrome and that is was probably permanent in nature, because it had been at least two years since I'd hit someone or someone had hit me. And so I walked out of the office thinking, will I live?

Because I thought, you know, I'd never heard of the condition before, I thought maybe it was something one of my teammates had had who I'd played with, and he said you can live with it, you just have to learn how to manage it.

SATALIA: You're referring to a friend who had the same kinds of headaches but his problem turned out to be brain cancer.

CARSON: Yeah, it was Doug Kotar, who is originally from Canonsburg.

SATALIA: Pennsylvania.

CARSON: Right outside of Pittsburgh, and that was my concern that I was dealing with the same thing and that's why I asked the doctor ‘Will I live?’ And so he said you have to manage it. And so over the years I've learned how to manage it but I've also paid very close attention to my own body and I've taken part in numerous conferences with the Brain Injury Association, I've sat on panels with some of the foremost authorities on head trauma and neurological disorders and so forth and I've learned a lot. And so I sort of came to this understanding that if I was dealing with this as a player there're probably a whole bunch of other players dealing with the same thing—and you know that was more than 20 years ago—and now there are just so many players who are dealing with the same issues; guys who I played with, guys who I played against and so many younger guys who also have had to deal with this issue of traumatic brain injury.

SATALIA: When we think of football we usually think of injuries below the head.

CARSON: Right.

SATALIA: In a recent survey of former players, 86 percent of them said that, post-play, they needed orthopedic surgery. Three out of ten needed five or more surgeries. So if they're in that kind of physical shape, what kind of neurological shape is the average retired football player in today?

CARSON: I can't really say because there are some players who are having some very serious issues and then there are others who are just sort of tootling along, they're doing very fine, but I think it also depends on what position you played. And those who played those contact positions, where they're being hit on almost every play, like defensive, offensive linemen, linebackers, running backs, those guys are probably having more problems than the quarterback who might just get hit occasionally or a wide receiver who doesn't get hit on a regular basis or a defensive back. So it sort of varies from position to position, but also from player to player. But I've seen a lot of guys who didn't get a whole lot of contact but then they've had problems. Dave Jennings who's a punter with the Giants—he developed dementia and Alzheimer's. And so you would think that a player who is not involved in a lot of contact probably would not have any issues, but it really does go right across the spectrum. You never really know who is going to have to deal with it.

SATALIA: We're learning that these sub-concussive hits can actually be just as damaging, so while it may not register as a concussion there are studies where they're measuring the impact and it may be a G8 force and that person is not…I'm talking about high school students now…they won’t have passed out, they won't have seen stars, and yet, it's the equivalent of a car wreck.

CARSON: Yeah, and you know if you're going to play you have to understand that those things are going to happen, it's football, and you're going to have to get up, get back to the huddle and continue to play. Football players have this mentality that if they can walk then they're going to play. Obviously if you have some kind of knee injury or ankle injury or something like that, that's going to impede your ability to be effective on the field, yeah you come off the field, but if you've been dinged and if you get your wits about you in time to, you know, for the next play, you continue to play.

SATALIA: You played with blurred vision yourself.

CARSON: Yeah, I played not necessarily knowing what the defense was and I was calling the play (chuckle). But that's all part of the game and unfortunately you sort of have to deal with the results of what you've done, you know, later in life and that's part of the reason why I've been so vocal about this, because when I played nobody told me that these things could happen. And because nobody told me I feel that it's incumbent upon me to tell other people, more precisely, the parents of young kids who may not necessarily know what they're signing their kids up for.

SATALIA: You know you might break a leg, you know you may dislocate a shoulder.

CARSON: Everybody understands that when you play the game that you are putting yourself at risk, physically, but no one stops to think about the neurological risk that you have to assume when you step on the football field, and that's where we are now.

SATALIA: And the NFL has recently acknowledged that 30 percent of players will receive some neurocognitive impairment.

CARSON: Yes they've acknowledged it and 20, 24 years ago when I first was diagnosed, and then when I first started talking about it, I thought eh, they'll never admit it in my lifetime. And so they've admitted it and I'm pleased, but I think with that admission, I think parents need to understand more clearly what they're signing their kids up for and what the NFL has said. I mean they've agreed, you know, one in three players will sustain some kind of brain trauma, that they might have to deal with for the rest of their lives.

SATALIA: You have said that the NFL's suit settlement for $765 million is 765 million reasons why you shouldn't play football.

CARSON: And now that figure is uncapped, and so now, the NFL has given everybody an uncapped reason. In essence you can't even put a dollar figure on it, the reasons why you don't want to play football. And I'm not telling people not to but I'm just saying you really should pay attention to what's going on because there is a cause and effect here and players who have played the game, not even on the NFL level, are dealing with mild neurological problems as they get into their 30's if they played high school and college football, but most of the attention is focused on the NFL player, you know, 40, 50 into their 60 year range, so you know you have to pay attention to what's going on.

SATALIA: There are more than 8,000 retired NFL players at this point; more than 4,500 have signed on for this lawsuit. You're not one of them, despite having Post-Concussion Syndrome. Why not?

CARSON: Well, I know what I have and I know what I've been living with, but I also know that it was incumbent upon me and a few other guys who have been diagnosed to share our stories, whether it was with Congress or with the media, or whatever, we needed to share our stories. And so I've done that, and the reason why I wanted to not be a part of the lawsuit is, once I sign my name, people will say, well the only reason why he's doing it is because he stands to benefit financially. Well I have no beef with the NFL; I work very closely with the NFL; I work very closely with the New York football Giants, but I am who I am and I know what I know and nobody's going to shut me up from saying what needs to be said. Now I'm not necessarily going to impose what I feel on you, but if you ask me, I'm going to tell you, and I'm going to be very open and honest with you if you ask. If you want a truthful answer, I will certainly give you the truth as I know it.

SATALIA: And your truth is…and in fact, you listened to Deacon Jones give an acceptance speech. I think he was inducted into Hall of Fame same time as you.

CARSON: No, he was inducted a few years before me.

SATALIA: Yes, okay, and he got up and said that despite all of his injuries, and despite all of his problems, he said I loved it and I would do it all again. And you said you were in the midst of repeating what he said and then realized ‘If I could, I wouldn't.’

CARSON: Yeah, yeah.

SATALIA: Really? Really you wouldn't do it all over again?

CARSON: Being in the Pro football Hall of Fame you're around many of the great players and those great players have absolutely no regrets and so when they get up and they talk about the game they say it and you can feel their passion as they're talking about it. And they'll say, you know, I played the game and there's nothing that I'd do differently and I'd do it all over again, and I sort of fell into that mold of trying to follow them. Yeah, I love the game too, and then I thought to myself, would I do it all over again?

I thought…

SATALIA: Knowing what you know now.

CARSON: Knowing what I know now? Oh, hell no! And so I had to get away, you know, I had to respect the opinions of other people. I know they love the game and they'd do it all over again, but for me, knowing what I know, I would not have played the game. And I'm firm with that. I don't say that to get headlines or anything like that, but any, and this is just me, any smart person who can see that there was something that created a problem for you later in life, would you do it all over again?

It really is not worth it to me.

SATALIA: The interesting thing about your story is that it was football that allowed you to get a Bachelor's degree in education from the University of South Carolina, and then you went on to get a Master's degree. So by the time you did all this you had so many options and your reality may be so different than it is for lots of other playes who go through college but really don't get an education.

CARSON: Well, I was fortunate in that I had people who pulled for me to get an education. I had a lot of training in football but also ROTC. So if I had not gone into football I probably would have been career service.

SATALIA: A pilot you said.

CARSON: Yes, and I always had this fascination with flying and I was from an Air Force family. My older brothers both were in the Air Force, but you know football sort of came calling and so I played the game. Now football gave me the opportunity to do some of the things that I've done, but in retrospect I've always considered myself a pretty smart person. Perhaps I could have gotten my education in some other way, perhaps the GI Bill, as result of the military experience, or whatever, but you know it is what it is, I played football and here I am.

SATALIA: And you are emphatic that your grandson will not play football.

CARSON: I am so emphatic; I am 110 percent certain that he will not play. If I have to pay for his education myself, he will be going to college. He's only four now, he'll be five in October. He will not be playing football to have to earn a scholarship to go on and get a higher education or, to hopefully one day, go to the NFL or anything like that.

I've already done that, okay. We don't need anyone else.

SATALIA: In the Carson family.

CARSON: Yeah, we don't need anyone else. I've got a Hall of Fame bust and you know we can put somebody's picture on my bust and there you go, but I know what it took to get there and I certainly would rather my grandson excel academically than athletically.

SATALIA: Is there anything that the NFL, the NCAA, Pee-Wee coaches, high school coaches can do to make the risk of the game acceptable?

CARSON: I think that the game is what it is. In terms of trying to make the game safer, I know the NFL is trying to make the game safer, I think the NCAA is trying to make the game safer, but it is the very nature of the game.

It's contact, it's about power, it's about speed, it's about guys colliding with one another on the football field; that's what fans like to see and that's the way that the game is going to continue to be played. It's a physical game and if you're not going to be physical then you shouldn't play.

SATALIA: You caused some concussions.

CARSON: Yeah.

SATALIA: I'm kind of curious about what your approach was to hitting other players.

CARSON: Well, it was my job to hit players, whether it be-I was trained you know? From the first day I stepped on the field, how to use your forearm to hit an offensive lineman right in the face and get him off of you and get to the ball carrier and make the tackle. And so I became very proficient in doing that. I was pretty good at what I did, and I became known as one of the hardest hitting linebackers in the National Football League. So you know I took great pride in that but then with the Mike Webster situation, then it became abundantly clear to me that I probably

SATALIA: Iron Mike of the Pittsburgh Steelers.

CARSON: Yeah, that I contributed to many of the issues that he had post-football and ultimately he passed away as a result of a heart attack, but you know I felt saddened because I felt that the way that I played the game against him

SATALIA: Him in particular.

CARSON: In particular, because Mike was known as the strongest guy in the

SATALIA: Iron Mike.

CARSON: National Football League. And so I had to meet force with force and so as I said, ball would snap, you know, he'd come to block me, I'd hit him in the forehead, in the head with my flipper and you know that took a toll on him later in life. And so in some ways I'm really saddened by that but I also feel that I contributed in some way, but if I was to ask Mike, or talk to Mike, he would say ‘Harry, I'm proud of you, you played the game the way it's supposed to be played;’ that's the kind of guy that Mike Webster was.

SATALIA: The interesting thing about the Pittsburgh Steelers is, in terms of their approach to concussions, they're more traditionalists, you get back in there and play, and that's in contrast to the Green Bay Packers who are more inclined to say If you're concussed, sit out. So I'm curious, is that changing—and is it different from franchise to franchise?

CARSON: Well, it's out of the hands of the team now because there are independent neurological specialists on the sideline to examine players, so if they sustain some kind of ding and they're examined, if that specialist deems that they should sit out then they're going to sit out. It really doesn't matter what the coach says.

SATALIA: They hide it, as you know, players hide it.

CARSON: Well players want to play, players want to play and they also know that once they've been diagnosed that's like the opening salvo to okay, you're damaged property, when the off-season comes we're going to have to find someone else who has not been damaged. And so they, especially on the pro level, it's about their paychecks, it's about their careers. College level it might be a different story. It might be that will just to play with the guys who you've practiced with all week, but guys want to play.

On the high school level that's like if you pull a player out and he can't play what he's going to think about is I won't have enough information on a tape to show to a coach coming by who can give me a scholarship. These kids in high school they want to go to college and they want to play on the collegiate level and eventually, hopefully for them, get to the NFL level. And so you know, once they're diagnosed and they're held out, it's like being stabbed in the heart. They really, really, really want to play.

SATALIA: You were very, very intimidating on the field. In fact, one

CARSON: I was a nice guy. I was really a nice guy.

SATALIA: But if you knocked someone down you weren't wasting energy helping a guy back up. But I'm just wondering, how difficult was it to leave that aggression on the field? And I ask that because of the scandal that is exploding within the NFL right now, Ray Rice and Adrian Peterson and I could go on and on.

CARSON: I think that in order to leave it on the field you have to, and let me just back up for a second. I probably never should have played football because my mindset was never that of a football player. I've always been a gentle soul, I wouldn't hurt a fly and so when I started playing football I had to flip a switch and be able to bring out that aggressive side. Otherwise you're not going to last very long, and so when I, when I played I learned that I need to flip that switch when I stepped on the football field, whether it was listening to the National Anthem or whatever, when I put the helmet on then I'm ready to go. When the gun sound or when the whistle blew with double zeros on the clock, then I have to let it go and I have to leave it on the football field.

But I can clearly understand how some players bring what they learn on the field, what they've been trained to do, home because when you're playing high school ball, it's a certain speed. When you're playing college ball that speed is increased significantly. When you get to the NFL you're like on a supersonic speed and every, I mean running a four-three or four-four or four-five you know, that is what you measure players by and so you have to be fast, and you have to be quick, but you have to make snap decisions.

You have to make a decision within a fraction of a second, not a second, otherwise that player is gone.

SATALIA: And it may be that fraction of a second that results in you pummeling a wife or girlfriend.

CARSON: Right, and when you find yourself in a situation that it starts to escalate with arguing or whatever, you have to understand where you are and what you're doing and you have to make a conscious decision to back away. Otherwise if something happens oftentimes it's like a snap second decision that you've made in whether it's hitting your significant other or whatever, but once you make that decision then you feel guilty about it and that's one of those deals where football sort of comes home with you, because you have to really be slow to anger if you're a football player.

As a captain with the Giants, that was my job on the football field, to make sure that my guys did not get into altercations and that they were slow to anger in such a way that the team is going to be penalized. But I also encourage the guys who I played with to do the same thing. Be very slow to anger once you step off the football field because things happen on the field where you have to respond just like that, but off the field you know you have to give it a little bit more time to process in your brain before you act on it.

SATALIA: You mentioned earlier, when you were talking about Post Concussion Syndrome, not being able to find the word you needed when you were in the broadcasting booth and headaches and things like that. You also mentioned depression--and even when you played there were times when you dealt with depression and (it's something you wrote in your book, Captain for Life) you kept that to yourself in part because players were traded and for a former player to go to a new team they could use that weakness against you. Are players today inclined to keep tight lipped about depression and aggression problems and those kinds of things that are really troubling them?

CARSON: I really can't speak for them; I just know how I had to sort of manage my life. I saw what I saw and I saw that if a player with the Giants, one of my teammates got cut and he went to a team I was going to play, he was going to spill his guts and tell everything that he knows because he wants to get back at the Giants. And so I learned just to keep my weaknesses, keep things to myself and not share and that sometimes that carries over into your personal life and it can be very difficult when you keep things to yourself and you have a spouse and you don't share certain things with your spouse.

And so I'm on my second marriage just like a lot of other players who may have played in the league, who once football is over you know had this difficulty making the adjustment. And so I've learned how to just sort of manage my life a certain way and what might work for me might not necessarily work for someone else, but as you sort of float through life you find ways to cope.

SATALIA: Is it avoiding stress? What is it that you do manage this Post Concussion Syndrome?

CARSON: For me I think very clearly about what I do. I think about what I say. I have to analyze every word before I let it leave my tongue and my lips.

SATALIA: Very controlled.

CARSON: Yeah I'm very controlled because you know you don't want something to come out that can be misconstrued or misinterpreted, mispronounced and so it's just the way that I cope with being me.

SATALIA: And you also have this experience that I think must be influencing that part of you that's so controlled. You said in the 1980's you were so depressed that you actually envisioned yourself or thought about driving over the Tappan Zee Bridge.

CARSON: Yeah.

SATALIA: Committing suicide.

CARSON: Yeah. I was playing the game and this has to be 1981 and I was feeling depressed and I'm thinking to myself why am I depressed, why am I feeling like this because here I was a football player, I was making nice money and I had a baby daughter but yet I would have these bouts of depression where I could sort of feel myself sort of slip into like this abyss and just sort of wallow there for a while and then eventually I'd come out. And I lived in Westchester Ossining New York and every day I had to drive across the Tappan Zee Bridge and so on my way to Giant Stadium, you know, I had thoughts of what if I drove off the bridge, what if I accelerated, and I thought about it a few times and I was like, no. What would happen to my daughter? And so I had those fleeting thoughts but it came down to my daughter sort of being my inspiration, and so I paid attention to it over the years.

And I can remember going to the Giant's training, Ronny Barnes, and we had won a game, I think this was 1988, my last year, we won a game and we have to, the day after the game go to the trainer and make sure we're on the injury report. And so I went to Ronny and I said, Ronny I just want to tell you that I'm depressed. He looked at me and he said well what do you want me to do about that? I said you don't have to do anything, I'm just sort of putting you on record.

At that point no one had ever told Ronny that they were depressed. And so I felt like the whole concussion thing played into the depression, and so whether it was depression, headaches, blurred vision, sometimes I would have twitches in my right arm and I couldn't figure out why is this stuff happening and then I came to understand that it was probably a result of maybe some kind of head trauma that I'd sustained playing the game, but you don't put those things together as you're playing.

SATALIA: But today of course you do.

CARSON: Yeah.

SATALIA: At one time boxing was the spectator sport; it's now football. Can the NFL survive this current scandal or do you think that this most-watched sporting activity is in its decline?

CARSON: I think the NFL will survive. There'll always be players who will want to play. In regards to the whole concussion issue there'll always be players who want to play, but I also think that the NFL will navigate itself around what is happening. They are masters at that and so it might take a little time but they're going to get the guys who are constantly being in the headlines for domestic abuse or even bullying or whatever.

They're going to have to get these guys out of the league and become a more fan friendly league, a more women friendly league, a more kid friendly league and they will do whatever they have to do, and this is just by belief, to rectify the problem.

SATALIA: Alright. Harry Carson thank you so much for talking with us.

CARSON: You're quite welcome.

BONUS INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT

SATALIA: You talked about playing injured and if you don't you don't last very long. The reality is that the average NFL football player plays for 3.3 years. A first round draft pick has a 9.7-year career. Here you are, you played 13 years.

CARSON: I probably could have played 20 if I really wanted to, because at some point your skills, your speed, your quickness starts to diminish but then you have the experience and you make up for what you do through the experience. Those who don't make it after three or four years, they've solely relied on their speed and quickness and so forth. So when it's no longer there they don't rely on what they've learned from the game to play smarter. And so some players if, like a Michael Strahan or Jackie Slater, who played like 20 years with the Rams, once they know what they're doing and they can physically handle themselves on the football field, they could probably play for as long as they want to play.

SATALIA: You retired in 1988, 26 years ago. The issues in your generation, the things you fought for then, for your teammates, was free agency. And I'm kind of curious how today's players feel about you and others who are fighting for the NFL and the NFL Players Association to provide benefits and those sorts of things to former players.

CARSON: I think some players of today understand that there were sacrifices made by players of my generation and they appreciate it, but for the most part most of the players who are playing today have no clue of the history of what preceded them. They don't care. It's all about them. And so it's about them getting paid. And so I feel sad for them because at some point they're going to become former players.

SATALIA: And sooner than they think.

CARSON: And sooner, much, much sooner than they think, but you know there are so many players who are singularly focused on what can I get, you know, right now and not worry about their teammates, not worry about winning, I mean surprising enough there are guys who aren't worried about winning, they're more concerned about being able to get that next contract, and that's the most important thing to them.

SATALIA: At your highest paid you made $550,000 a year, which is probably $11 or $12 million today.

CARSON: Yeah.

SATALIA: Which is a lot to smile about. But how does it compare with today's salaries.

CARSON: Oh there's no comparison because I don't even think that's the minimum for some players. You know $550,000 to me was a lot of money but compared to what players are making now, I mean it's practically nothing. But I say this and people often ask me do you think that you missed out by playing when you played and I say no. I'm glad I played when I played because when I played, if I did my job, I would have a job.

I knew I would have a job. Now you can do your job and still lose your job simply because of how much you make, and if a team comes to you and says we need, you didn't have such a good year so we need some of the money that we paid you for next year, we need some of that back. And if you don't take a pay cut then you're out and they get rid of you. Now you can do your job and not have a job and then be ushered out of the league. There are a lot of guys who are home now who could still play. They're not hurt, everything is good, but because they made too much and they weren't willing to take a pay cut and they were sticking by their own principles, you know, they're at home now.

SATALIA: How did you feel about Gene Upshaw before he died, of course he was the head of the NFL Players Association, who said that his responsibility was not to former players? He's being paid by these current players.

CARSON: Well Gene was responsible for the livelihood of the retired players because the retired players were sort of under the roof the NFL Players Association, but when you are negotiating for the current players and they've hired you, they pay your salary and the retired players don't pay your salary or it doesn't, whatever you're being paid from the retired players is, you know, pennies compared to what you're making from the current guys, you're going to lobby more vigorously for the guys who are paying you the most money.

And so with some of the comments that he made, the retired players took offense to it. I've always liked Gene, even when we played against one another, but I didn't feel that the retired player's community had its full confidence in Gene being their advocate, and I told him that we did not feel adequately represented. And so he begged to differ and when he passed away I think that a lot of the progress that had been made in regards to retired player issues, whether they be benefits, but also pensions, I think much of that came from Roger Goodell as opposed to Gene Upshaw and or DeMaurice Smith, the current Head of the NFL Players Association.

I could be wrong, but you know, I had conversations with Roger and he was committed to helping the plight of the retired players. That was one of the things I spoke about when I got up to give my acceptance speech in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, for the NFL to do a better job of taking care of its own.

SATALIA: Do you think Roger Goodell will survive the current scandals?

CARSON: Well I think he will. He works for the owners and I think the owners have trust in him and they're the only ones who can fire him unless there's something that I don't know about today that might come out, I think that he will probably keep his job.

SATALIA: I'm curious to know—do you have plans to donate your brain to science once you die, to see if you, in fact, have any of these tau proteins that are indications of CTE (Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy)?

CARSON: I'm pretty sure I've got something, so what doctors need to do is come and talk to me now while I'm living but I have no plans of donating my brain to anyone, because I feel like my brain would just be another brain, and I'm pretty sure there's something going on up there, especially the left front temporal lobe, I'm pretty sure there's something going on in that region, but I don't think doctors having my brain and sort of slicing it up is going to tell anyone anything new.

Because I was diagnosed in 1990, I've talked about it, if it looks like a duck, if is quacks like a duck, if it waddles like a duck, it's a duck, so I've already got it I'm pretty certain. But I've learned how to live with it and that's the tragedy of many of these guys who have committed suicide that you can live with it you just have to learn how to manage it.

And let me just say it's not just players who have played in the National Football League or football period, but also many of the soldiers who have returned from battle who are taking their lives because on the average there are 22 a day.

SATALIA: Wow.

CARSON: Soldiers committing suicide. So if they're dealing with bouts of depression or whatever, they can find a way to live through it.

SATALIA: I have one final question for you. You have been honored in so many ways throughout your life. You were named the Number One Linebacker in NFL history, you were inducted into the

CARSON: Inside Linebacker.

SATALIA: Okay, inside Linebacker. Of course you were inducted into the Hall of Fame, but I'm wondering for what are you most proud?

CARSON: I am most proud of, me personally I'm proud to be the person that I am, to be able to share my life with people openly and honestly. I went to school to become an educator and so I wound up playing football and in so many ways I'm able to educate people through my football experiences and what I'm going through now, and what I've been able to do is be a resource to so many other people who I don't even know around the world. Sisters of brothers who have committed suicide, wives of former players who are now dealing with becoming caregivers and so forth, you know, I'm happy that God has placed me in a situation, where you know, my life is good. I can't complain about anything, but yet I pay attention to my own body and I also know what's going on with my body, and as long as I take care of me then everything is good. Get up in the morning, go to the gym, get that latte from Starbucks and I'm able to live a pretty normal life in spite of the issues that I've dealt with over the years.

SATALIA: Harry Carson, thank you so much for talking with us.

CARSON: My pleasure.