With an increasing number of opioid overdoses in Pennsylvania, attention from state and local officials is growing as well as public attention around the issue. In 2015, there were more than 3,500 drug related overdose deaths in the state, which marked a sharp increase from the previous year. In Philadelphia, 900 people died as a result of overdoses, which is three times the number of homicide victims.

Nicole O’Donnell is 37-years old and outgoing. She lives in Delaware County with her fiancé and is a working mother of two.

“I was very lucky. I was blessed. Twelve years of Catholic school. Good student. I had friends. I played sports. My parents are still together. But there was always something missing.”

Looking at her, it’s hard to believe she spent her 20s in and out of rehab, survived a suicide attempt, and two heroin overdoses.

“I took — probably it was Xanax — the first time. It took away anything that I thought I was stressed about. I thought that it helped me get things done. It gave me this false sense of accomplishment.”

Her darkest days were spent shooting up, squatting in an apartment and eating scraps from a dumpster in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, which many consider an open air drug market.

“The party is over by the time you start shooting heroin. You need to use before you eat. I remember just praying to die.”

Nicole has been clean now for eight years; and today she works as a youth recovery specialist. She also volunteers with a nonprofit called Angels in Motion started by Carol Rostucher.

While there are nearly 150 volunteers with the organization, Carol and her friend Barb Burns are on the streets everyday, driving around in her beat-up Toyota.

Carol spent five years looking for her son on the streets of Kensington; where he would come and go to buy drugs.

“Not that there’s one type that becomes addicted. But the thrill-seekers seem to be more prone to it. My son was definitely a thrill-seeker his whole life. A lot of people do start with just partying and having fun. His partying and him having the disease of addiction — I believe it’s a disease and he has that disease — just led him to keep going deeper and deeper into the drugs. Even though he realized how bad it was, he couldn’t stop. I could see it in his eyes when he would sit and talk to me. I could see the fear. I could see the sadness. I could see the despair. Then, he told me the day he tried heroin, he knew that was it. He was done.”

Carol’s son has been in recovery for two years now, but she still spends every day in Kensington with Angels in Motion. For those on the streets that are willing, she helps to find housing and treatment.

One of Carol’s kids, as she likes to call them, is Earl. He’s terribly thin and his eyes shift back and forth. He talks with a gruff voice and curses a lot. But ask anyone who knows him, and they’ll say he wouldn’t hurt a fly. Four months ago, Carol got Earl into an apartment. He had been homeless for nearly 20 years.

While sitting in Carol’s car, Earl talked about growing up in Kensington surrounded by poverty and drugs.

“Both of my parents were drug addicts. I lost both my parents to drugs. But I do them; and I do hate and despise them. I can’t stand drugs. Really I can’t. I started dibbling and dabbling a little bit here and there. Snorting it; and one thing led to another. I had a major habit, and I’ve been fighting with it for 16 to 17 years. I’m still fighting with it. I want to say that I’m so at unease with life. I feel like I have to be high on something; now that I’m addicted to heroin — destroying my life. I’m 41 years old and I got a lot of life, I guess, to live. But the question is: will I ever be free? I feel like I’m stronger than this and I shouldn’t have allowed this to happen. But it just happens. It’s crazy. Once you get involved, it’s so hard to get out. The only way out of this is death.”

At this point, Carol interrupted Earl to point out the progress he’s made.

“You don’t even see the steps you’re taking already. I’m looking at your face right now. You’re clean-shaven. Your hair is done. You’re clean. You smell good. You don’t smell homeless anymore, Earl. That’s a step. That’s a huge step. You have a heart of gold. You’re a good person. You’re going to make it. But you didn’t get here overnight. You’re not going to come back overnight; but you’re coming back, baby. You’re coming back.”

Earl responded to Carol, “I hope you’re right.”

“You are coming back,” insisted Carol.

Earl broke down in tears.

“I hate this. I hate waking up all sweaty and saying, where am I going to get my next bag?”

“Let’s talk about going back to the clinic,” suggested Carol.

One afternoon, Carol and her friend Barb Burns were doing outreach in Kensington; when they spotted what they thought might be a person on the ground in McPherson Square Park.

Barb rushed out of the car and saw his face was blue. She knew he was overdosing and gave him a shot of the reversal medication Narcan; then she began mouth-to-mouth. Carol performed CPR. Barb gave him another dose; this time a nasal spray version.

The women stayed calm but yelled loudly; trying to communicate with him as they slowly brought him back to life.

Reversals like the one Carol and Barb performed are becoming more common in Pennsylvania. Narcan is carried by first responders, outreach workers and nurses. It’s kept in schools; and even other drug users carry Narcan and are trained to use it.

In Delaware County, Ridley Township police officers have all gone through Narcan training. Sergeant Robert Crespy has been on the force for 27 years and has saved two people from overdoses.

“Part of the training was for us to get out of that mindset that drug addicts aren’t worth saving. They’ve climbed to the bottom of the barrel. I never looked at it that way personally, but I could see where officers would. I mean, their attitude towards it has changed. Saving a life is just as important to someone that has a heart attack, and perhaps you can administer oxygen or do CPR.”

Nicole O’Donnell, who has been clean for nearly eight years but had overdosed on heroin twice, says being saved with Narcan was traumatic both times. She remembers waking up in the hospital.

“The nurses were not nice either time. I was released minutes later when I came to. I remember being so vulnerable. You internalize that and you start to believe that you’re this horrible person; when in reality, we’re sick.”

How overdose patients are treated is something that concerns Sheila Dhand. She started working as an emergency room nurse in 2012.

“There is just more of a focus on your patient assignment. We have to move quickly. It’s a hospital, so they’re constantly pushing, pushing. Get this bed empty. Get this person discharged. Get this person admitted. Move this person along. There are some staff that are wonderful; but sometimes people are mistreated. Treated as less than a person for their lifestyle. I thought it was really disturbing and really upsetting. It could negatively affect their health.”

It was her experience in the ER that brought her to Prevention Point: a social services organization in Philadelphia.

Sheila would go there after work and hang out like a pesky little sister; asking staff if they needed anything. Now, she coordinates their wound care clinic. Each Tuesday, she heads out in a van with a team to treat some of Philadelphia’s most vulnerable citizens.

“The reason why I became a nurse, I wanted to connect with people and connect with a community of people. It’s chaotic because it’s catering to a community of people who tend to have chaotic lives. It’s like a topsy-turvy ride. There’s like some really good highs, and some lows. But overall, I think it’s worth it.”

As the opioid crisis continues to make headlines, Sheila is on the frontline of the epidemic and is challenging people to think differently about it.

“The perception is that people who use are violent. They’re criminals. They’re dirty. If you go to different sites around the city, you’ll see somebody who is: taking a break from work; driving in their car; picking up their syringes; going back to work; has a home; has a family; and is also using. It’s just that certain people have the ability and the privilege to be able to hide it better. You know, having conversations and meeting people who are using can really create a lot of empathy. It just takes away this fear of the unknown and opens people up to, ‘Oh, this person isn’t that different from me.’ They have an aspect of their life that maybe is really different from me. But when it comes down to it, maybe they identify as a friend, a mother, a child, and they’re human beings. I think that’s kind of at the core of it.”

While the opioid crisis escalates, families are struggling to cope.

As a mother, Carol Rostucher has dealt with a lot. She survived cancer while raising two boys on her own, but she says her oldest son’s heroin addiction was the scariest thing that’s ever happened in her life.

“Your first instinct is I can fix this. I should be able to fix this. I’m his mother. I can do this because a mother’s love trumps everything. But guess what? You can’t. That disease is so strong, it takes mothers from their children.”

Carol is grateful each day that her son has been in recovery for over two years now. Meanwhile, not all mothers are able to say that.

In her small brick house in Pittsburgh, Josie Buriak keeps photos of her son Max on the wall. After losing his tech job on Wall Street due to his heroin addiction, Max came back home to live with his mom.

“It was for me — being his mother — just so painful to know that there wasn’t really anything that I could do; and that I kind of knew how it was going to end. The door was unlocked; and for some reason, something told me to go upstairs and he was there. I think he was already dead.”

Even before Max died from an overdose, his addiction had spiraled out of control. Josie says Max stole from her.

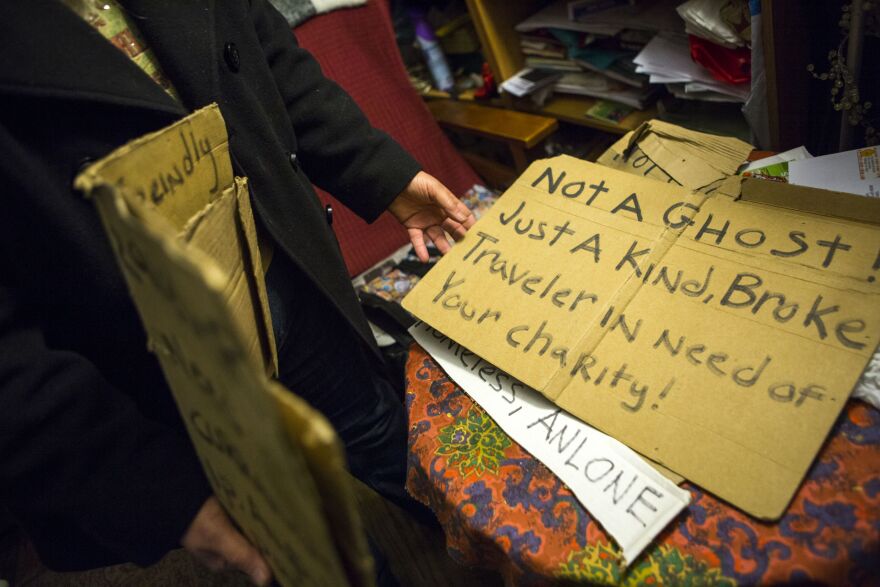

“He kept a lot of things from me. I didn’t even know he was standing down at the bridge — begging for money — until I was on a bus driving by and seeing him standing there. And it was like, ‘Oh my God.’ There’s another side to that. If he’s begging for money, that’s less than I have to give him. Your thinking gets so screwed up.”

But Josie and Max had a close relationship through it all. They spent nights watching TV and movies together.

“There was one evening — and I don’t even know how I had this extra money — we got a pizza. And I said, ‘You know, I feel almost like a human being again; doing something normal.’ And he says, ‘Yeah. That’s exactly how I feel, too.’ I know he loved me through all of this; and I know that it was hurting him, that he was doing what he was doing.”

For recovering addicts like Michelle, who are trying to stay clean, becoming pregnant complicated her life further. Michelle, which is not her real name, is 24-years old. When she found out she was going to have a baby, she’d been clean for seven months. She was happy and working a 12-step program. Then, things changed after she heard her best friend died of an overdose.

“I woke up, and I just decided to use that day. I didn’t know how to deal with what I was feeling. I was confused about how I was feeling. You question. You don’t know if it’s because you’re pregnant; or if you’re going crazy. But I am an addict. So sometimes that happens. That’s the best way you know how to not feel what you’re feeling. And I definitely didn’t want to feel what I was feeling anymore. It was just too much. It was too overwhelming. That’s when I moved back to my parents. You know my mom gave me the ultimatum: you need to leave; I’m going to kick you out, or you need to go to the clinic. So I did.”

Since then, she’s been getting outpatient treatment at Pregnancy Recovery Center at Magee-Women’s Hospital in Pittsburgh.

Michelle said, “I don’t want my daughter to grow up without her mom, and then having to eventually learn that I had passed away because of a heroin overdose.”

For Nicole O’Donnell, being a mother while struggling with addiction, has involved a steep learning curve. Growing up, Nicole was a straitlaced kid through high school; and then at 19, she had a baby and started to party. Her parents, who live outside Philadelphia in Delaware County, ended up raising their granddaughter for the first nine years of her life.

“Nobody leaves their children because they want to leave their children. I thought that I was never going to be a fit mother. I wasn’t the mom that she deserved. I wasn’t the mom that I could have been for her. So that’s guilt that I have to deal with.”

Now 37-years old, Nicole has continued with her recovery and is working full—time while planning her wedding and raising children.

“It’s been a whirlwind. Sometimes I can’t believe stuff that I’ve accomplished in the last year. You feel bad saying good things that you’ve done; because you remember where you were and how horrible things that you did were. But I also have to remember I have compassion for other people that are sick and suffering. I have to remember that I was sick and suffering, instead of feeling guilty. Turning that around is still tough for me.”