Crystal Weimer’s nightmare began in 2004, when she was arrested for a crime she didn’t commit.

“When you go to jail, your whole family goes to jail,” Weimer said. “It’s just like a ripple effect — it’s just not you.”

She was charged with the murder of Curtis Haith, a 21-year-old who dreamed of becoming a chef. Haith was shot in the face and beaten to death in front of his home in Fayette County, about 50 miles south of Pittsburgh.

Weimer, a single mom of three young girls, couldn’t afford the $50,000 it would have cost her to hire a private attorney. So she turned instead to her only other option for counsel, the Fayette County Office of the Public Defender.

As Weimer later learned, defendants in Pennsylvania who take that option often have the odds stacked against them.

A months-long investigation by Keystone Crossroads found an inequitable, heavily burdened, patchwork system that leaves Pennsylvania’s most vulnerable residents at the mercy of county governments that receive zero higher oversight.

Under the U.S. Constitution, if you’re charged with a crime and unable to hire an attorney, the sixth amendment ensures your right to an adequate defense.

In precedent stretching back nearly 60 years, the U.S. Supreme Court has said it’s up to the states to guarantee that happens.

Forty-nine of them allocate state funds for public defenders. And, usually, the money is tied to oversight and standards.

The odd one out is Pennsylvania, which leaves the responsibility to its 67 individual counties — an arrangement that has drawn criticism from criminal justice advocates for decades.

‘Unacceptable’

While the ramifications of Pennsylvania’s lack of funding and oversight for public defense are far reaching, to Crystal Weimer they came to a head in her case set in Fayette County, population 136,606.

When police first brought charges against her, Weimer said she wasn’t too worried about the outcome of the case. She knew she was innocent, and wasn’t even in the same town when the murder happened.

And after a jailhouse witness was caught in a lie, the charges against her were dismissed. But the ordeal was far from over, only just beginning — one that continues to haunt her to this day.

Five months later, police arrested Weimer for the same crime – and this time, the charges stuck.

“Here they come, five months later, knocking on my door, ‘Crystal Weimer, come with us.’ Here you go again,” she said.

Weimer faced up to 30 years in prison for third-degree murder, aggravated assault and other charges.

The prosecutor offered a deal that would set her free in just a few years — if she pleaded guilty.

Weimer says a representative from the public defender’s office repeatedly visited her at Fayette County Prison, asking her to accept the plea.

Plea deals are a way for lawyers to conclude cases faster and move to the next one.

But Weimer resisted.

“I’m not accepting something I didn’t do,” she said.

By rejecting the plea and pushing for trial, Weimer was putting her fate in the hands of a public defender — attorneys who, statewide, spend two months less time on cases compared to those in private practice, according to a Keystone Crossroads analysis of data from the Administrative Office of Pennsylvania Courts.

“Most private attorneys have paying clients who can also afford to pay their bail. Public defenders often represent people who are detained,” said Nyssa Taylor, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union. “If you are detained you are far more likely to want to get the case over with. You are far more likely to take a guilty plea.”

Weimer didn’t take a plea – and then sat in jail awaiting trial for two years.

“Two years! Two years before I went to court. Before I did anything!” she said. “They call Fayette County [Prison] ‘Fayettenam’ because it’s like Vietnam. It’s so horrible there. They had me stuck in a basement. The living conditions were unacceptable.”

At the trial, the prosecutor put on a convincing case with testimony from expert witnesses.

One used a photograph of a possible bite mark on the victim’s hand to tie the murder to Weimer, saying the image matched molds of her teeth.

Still, Weimer believed the jury would see that she was innocent.

When it came back with a guilty verdict, she was in shock. On April 19, 2006, Weimer was sentenced 12 to 25 years in prison.

“It was a nightmare,” she said.

Misstep?

Weimer’s conviction might have been avoided if not for what she believes is a major misstep in her case. Remember, Weimer was arrested for Haith’s murder before, and the charges were dismissed.

At that time, the Fayette County Public Defender’s Office could have tried for a dismissal with prejudice, meaning the charges would’ve been dropped forever.

But that didn’t happen.

“What do you call it, malpractice? What do you call an attorney that doesn’t do their job properly?” Weimer said.

We’ll never know whether the judge would have agreed to dismiss Weimer’s case with prejudice.

Fayette County Chief Public Defender Jeffrey Whiteko, 25 years in the role, didn’t push for it.

He says now that he can’t remember all the details of the case, but that his office did everything it could.

“Our attorneys put every effort into it that they can and some of the people, no matter who they’d have as an attorney — they’re still going to be found guilty,” Whiteko said.

During his tenure as a public defender, Whiteko has seen calls for statewide reform go unanswered, and he’s become hardened to the status quo.

“I’m not going to beat myself up for this. I’ve been beating myself up for 33 years on this,” he said. “It’s not going to change until the state takes over the system — which I don’t see them ever doing – it’s not going to be a fair fight.”

‘Vast scheme of things’

Weimer’s case unfolded in the mid-2000s, a few years before Pennsylvania’s Joint State Government Commission began a study of the state’s public defense system.

In 2011, it released a scathing report based on 2008 data that found — among other things — that the state’s lack of supervision and training for defenders means some offices are not properly serving their clients.

Now, after speaking with dozens of sources around the state, filing more than 100 right-to-know requests, sorting through thousands of pages of documents and analyzing dozens of data sets, Keystone Crossroads found that the situation has not improved and, in some ways, is worse.

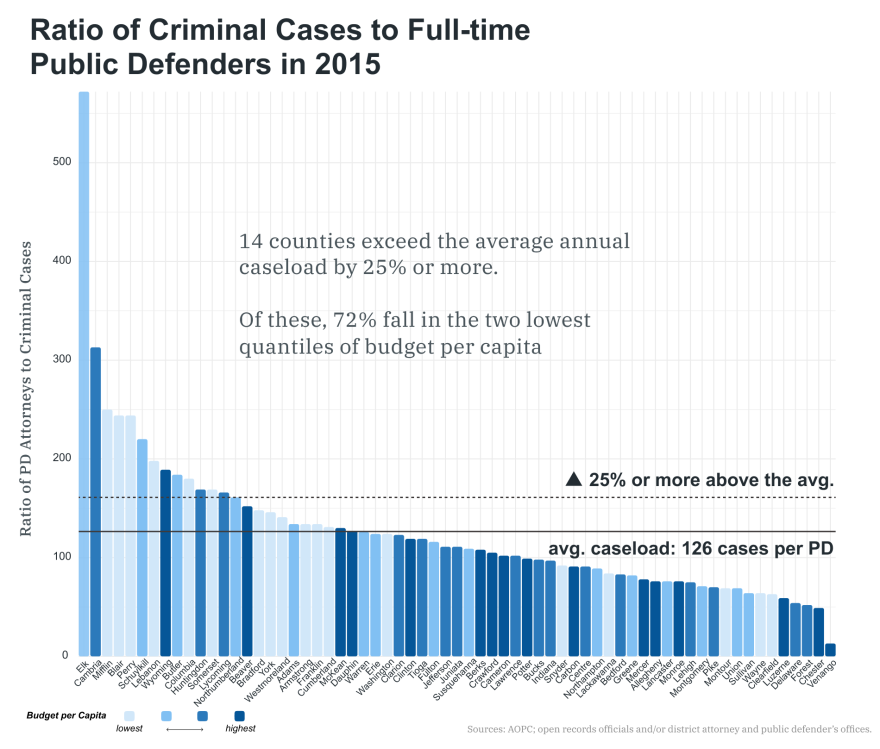

Even as the crime rate and criminal caseloads have gone down generally, the burden on public defenders statewide has gotten heavier — in some counties doubling.

The amount public defender offices spent on each criminal case varied between hundreds of dollars in some counties and thousands in others, according to our analysis of budget data.

Yearly caseloads also varied widely, between dozens or hundreds per public defender, depending on the county.

But it’s tough to get a fair and accurate comparison. Some county public defender’s offices handle much more than criminal cases and relatively few track the other types.

Again, the state does not collect data, monitor outcomes or set standards. So it’s difficult, impossible even, to fully figure out the statewide scope of the problems.

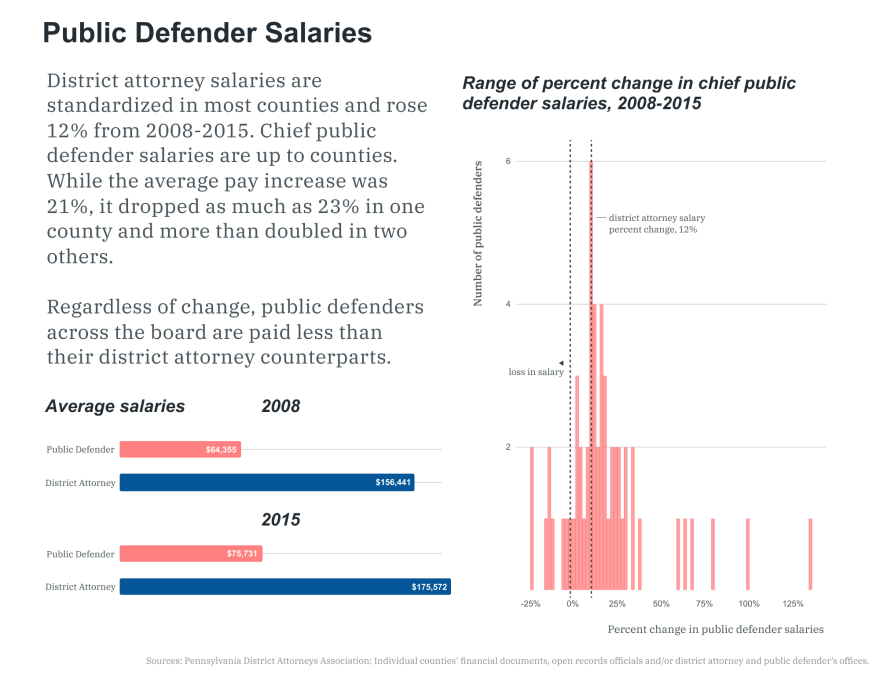

Our analysis of the data found one constant: chief public defenders are paid a fraction of what their counterparts get to head the district attorney’s office — on average a $100,000 difference.

“One of the key principles of indigent defense is that there should be parity between a cross prosecution and defense — equally-qualified, good lawyers for both sides,” said Carl Reynolds, senior legal and policy advisor for Center for State Government’s Criminal Justice Center.

There are other ways to track the disparities.

For instance, statewide, from 2008 to 2015, counties increased spending by 18 percent for public defender offices and by 24 percent for district attorney offices, our analysis shows.

But, due to both the lack of uniform data and the difference between the responsibilities of the D.A. and the P.D., some metrics could not be compared reliably. For these reasons, our attempt to compare total budgets, staffing and caseloads between D.A. offices and P.D. offices proved challenging.

Salaries are a more straightforward, if imperfect and only partial, way to measure parity.

In Pennsylvania, chief D.A. salaries are set by state statute, and the state reimburses nearly every county for two-thirds of it.

Counties, though, are on their own for all salaries related to public defense, as well as pay for assistant district attorneys.

Differences in starting salaries between assistant defenders and assistant district attorneys tended to be negligible, according to our analysis. There was a bigger departure between top rates of pay, with defenders getting less.

To Whiteko, this all stems from politicians who campaign as being tough on crime, and then don’t make public defense a priority.

“If you have an even playing field there’s going to be winners sometimes in the public defender’s office … and that doesn’t bode well for anybody,” he said, “because then the rate goes down as far as a conviction rate.”

Asked who is most affected by this set-up, Whiteko didn’t hesitate.

“[It’s the person] being represented,” he said. “But that’s a small person in the vast scheme of things, right?”

‘Not just laying down’

In Weimer’s case, her public defender faced resource constraints that affected the proceedings. And despite the defender’s efforts, Weimer ended up in jail for a murder she didn’t commit.

While in prison, Weimer wrote letter after letter — by hand — to anyone who would listen. She learned her case and went through several appeals.

They were all denied.

“Ohh, I was determined,” Weimer said. “I’m not just laying down and just being okay with this. I’m motivated. I’m getting out of here. That’s where I started writing and fighting and learning my case.”

After nearly a decade locked up, one of Weimer’s letters landed on the desk of Nilam Sanghvi, legal director at the Pennsylvania Innocence Project, based in Philadelphia.

They’ve received thousands of requests from inmates who say they’re incarcerated for crimes they didn’t commit.

“The thing that stands out to me the most,” Sanghvi said, “[was] this consistent refrain of, ‘I’m a mom of three girls. I didn’t do this. I need to get home.’”

After investigating Weimer’s case, Sanghvi and a team of attorneys believed her to be innocent.

As they looked at her case more closely, it fell apart. Jailhouse witnesses recanted their stories, soil samples were tossed out of court, and testimony from that expert, who claimed the bite mark matched Weimer’s teeth, was debunked as “junk science.”

“As a defendant without money you are facing so many battles and getting adequate representation and the resources that you need is one of the main ones,” Sanghvi said.

In Weimer’s case, her public defender didn’t even have direct access to a computer — let alone money to hire investigators and experts to fully disprove all of the testimony that was later thrown out.

“How were they supposed to take on all of these complex scientific issues when it’s part-time, they have very little funding?” Sanghvi said. “They made decisions that we may disagree with or do differently, but I think a lot of that is resource related.”

In terms of finances, Fayette County is not an outlier compared to the rest of the state.

In fact, while Weimer was in prison, the public defender’s budget in Fayette County fared pretty well compared to other counties.

It more than kept pace with the increase in cases from 2008 to 2015.

Elsewhere in the state, funding lagged behind rising caseloads: public defender budgets were up 18 percent while cases were up 27 percent during the same timeframe.

Still, those who know the Fayette County Public Defender’s Office best have reservations about the status quo.

Its leader, Whiteko, encourages clients to hire a private attorney if they can come up with the money.

“They’re going to be able to hold your hand more. They’re going to be able to talk to you more. We don’t have time. We cut through all that the bull-crap,” Whiteko said. “We don’t have time just to answer the same questions over and over again. They would.”

Damage done

Crystal Weimer couldn’t afford a private attorney and spent nearly 12 years in prison for a crime she didn’t commit.

On June 27, 2016, she was exonerated and all charges were dropped — permanently.

“If somebody would have investigated this crime from the beginning or had the money to hire a private investigator, this injustice would have never occurred,” she said.

Now, Weimer strives for her life to be normal again. But the lasting effects from being incarcerated make it difficult.

At 41, She’s trying to repair her relationship with her daughters.

“For twelve years of my life — being away from my family and my three little girls — my oldest is still mad at me,” she said. “You can’t replace stuff like that. The damage is already done. I can’t take it back.”

She has arthritis in her back from lying on a prison bed. She struggles with PTSD and has anxiety. She fears she could be ripped away from her family again.

“Someday it’ll be over. But it may not never be — until I die, you know,” Weimer said. “And I am gone, in a way.”