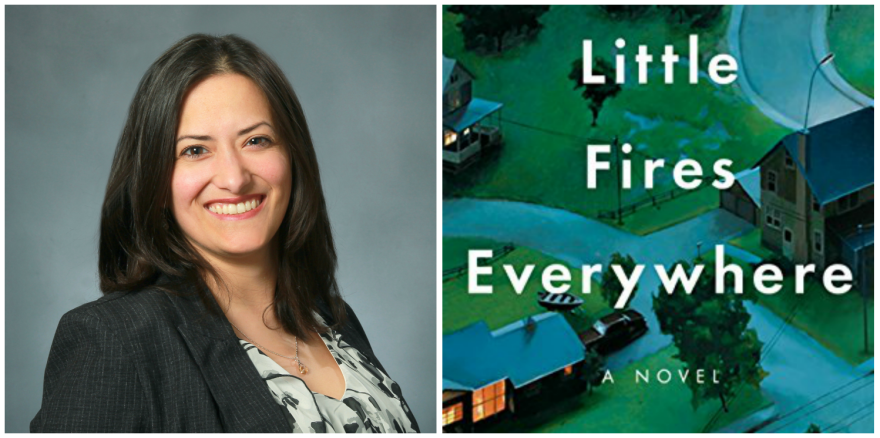

Celeste Ng’s latest novel, “Little Fires Everywhere,” revolves around a central question: what makes a person a mother?

The novel begins with the Richardson family—Mr. and Mrs. Richardson and their children Lexie, Trip and Moody—standing outside their burning home as firefighters attempt to salvage the remains. Mrs. Richardson’s youngest daughter, Izzy, is nowhere to be found—and, as the troublemaker in the family, everyone suspects she set the fire. Meanwhile Mia and Pearl, the mother and daughter who had been living in the Richardsons’ rental home for the past eleven months, have packed up their belongings, dropped off their keys, and fled the area…

Ng opens her novel with the fire, but she then goes back to Mia and Pearl’s arrival to explain how the fire started.

Mia and her fifteen-year-old daughter, Pearl, disrupt the status quo in 1990s Shaker Heights, a planned community in suburban Cleveland. And everything is planned, down to the colors residents can paint their houses. This by-the-book existence is a far cry from Mia and Pearl’s past. Mia, a fine arts photographer, is accustomed to moving from city to city with her daughter. But this time is different. Mia has promised they’re in Shaker Heights to stay.

Mia and Pearl’s lives are soon hopelessly entwined with those of the Richardsons, but maybe things could have continued as they were—had Mia not inserted herself in the affairs of Bebe Chow, a Chinese immigrant, and Linda McCullough, one of Mrs. Richardson’s closest friends. Linda was in the final stages of adopting a Chinese-American baby who had been left at a fire station when the mother, Bebe, surfaces and sues the state for custody. Bebe left her daughter in a moment of desperation and had been trying to find her ever since. A fierce custody battle ensues, and Ng shows how the residents of Shaker Heights find themselves divided:

“A mother deserved to raise her child. A mother who abandoned her child did not deserve a second chance. A white family would separate a Chinese child from her culture. A loving family should matter more than the color of her parents.”

Mia and Mrs. Richardson find themselves on opposing sides.

When Mrs. Richardson discovers that Mia works at the Chinese restaurant where Bebe is a waitress, she quickly realizes who must have told Bebe where her daughter was. She becomes indignant. She vows to unearth secrets about Mia’s past, comforting herself with the idea that she’s doing it for her oldest friend.

Within this larger story are several others that work to answer Ng’s question of what constitutes motherhood. She hits the topic from all sides, including abortion, adoption and surrogacy—and she reveals that these issues are rarely ever black and white. In “Little Fires Everywhere,” Ng writes, “Here… everything had nuance; everything had an unrevealed side or unexplored depths. Everything was worth looking at more closely.”

The same can be said of Ng’s novel.

Reviewer Adison Godfrey is a graduate assistant at WPSU.